No Place to Hide: The Struggle of Micro-details

Video Shooting in Progress

Now that the Holiday Market is over, 2025 has wrapped up, and some of the paperweights have left my hands, I can finally admit something.

I struggled immensely designing this tiny object.

That might sound ridiculous. As an architect, I am used to dealing with masterplans, site constraints, and structures that weigh thousands of tons. I usually work at a scale of 1:100, 1:500, or even 1:1000. At that scale, a line on a piece of paper represents a thick concrete wall; a box represents a building.

But for the<On Weight>exhibition at Songeun, the rules changed.

Colour Testing

When a Line is Just a Line

At a scale of 1:1, there is no abstraction. A line is not a symbol for a wall—it is just a groove in the metal. It might have symbolic meaning or rhetoric, but it isn't a representation of something else. It is the thing itself.

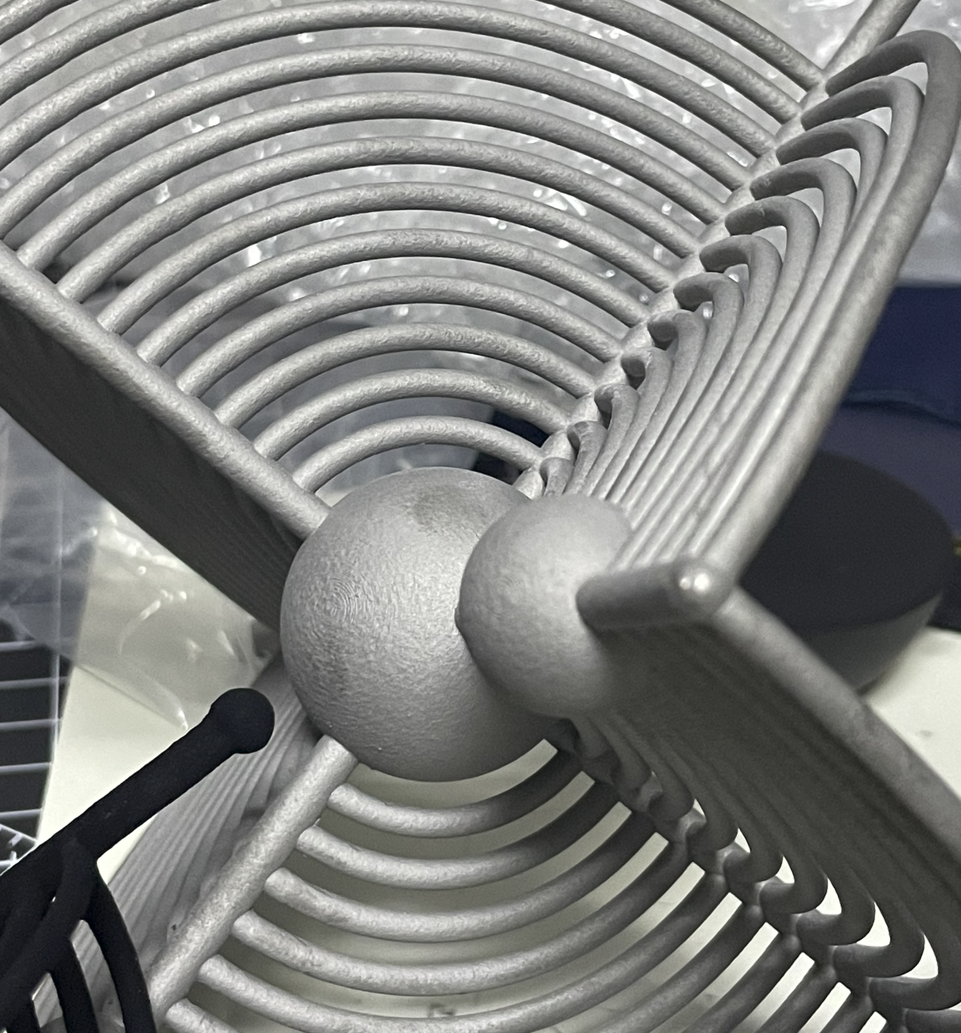

With an object that sits in the palm of your hand, there is no place to hide. A millimeter difference isn't a "tolerance issue"—it is a mistake you can feel with your thumb. When you zoom in that close, the stakes feel surprisingly high.

I wanted to share the traces of this project—the versions that didn't make it to the exhibition table.

The "Priorities" and The Detours

From the very first meeting, I thought I knew exactly what I wanted to do. Even though the scale was drastically different, I believed my architectural process would translate. I started the way I always do: by setting priorities. In architecture, this means knowing the legal framework, the site clauses, and the client's budget.

For this paperweight, my priorities were:

To be heavy (the fundamental duty of a paperweight).

To be different (from the other designers and my own past work).

To use a new material (something I was unfamiliar with).

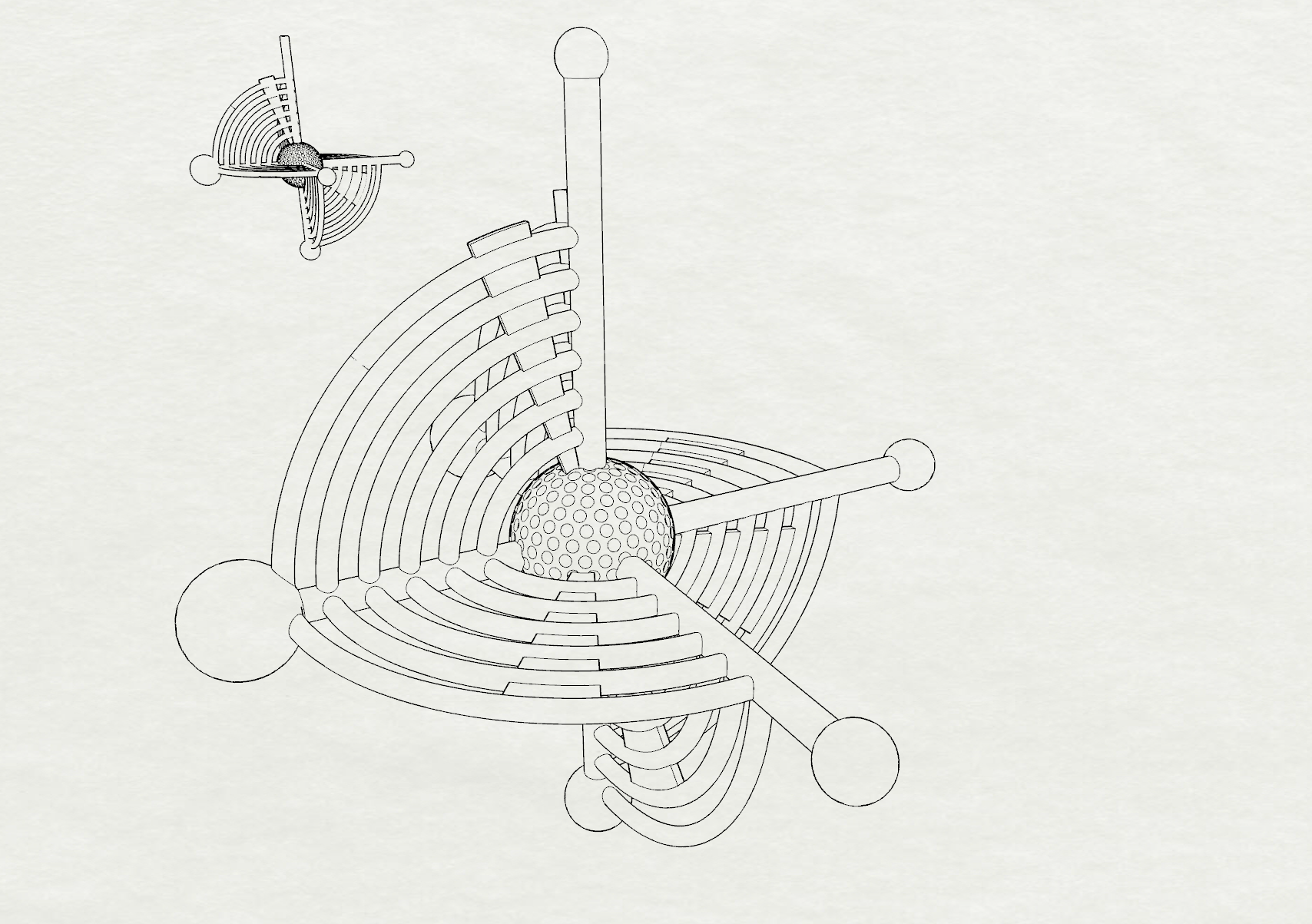

But the path wasn't straight. Because I wasn't designing a building, my mind wandered into "function." At one point, I wanted it to hold a pen. At another, I wanted it to spin like a fidget toy in the center.

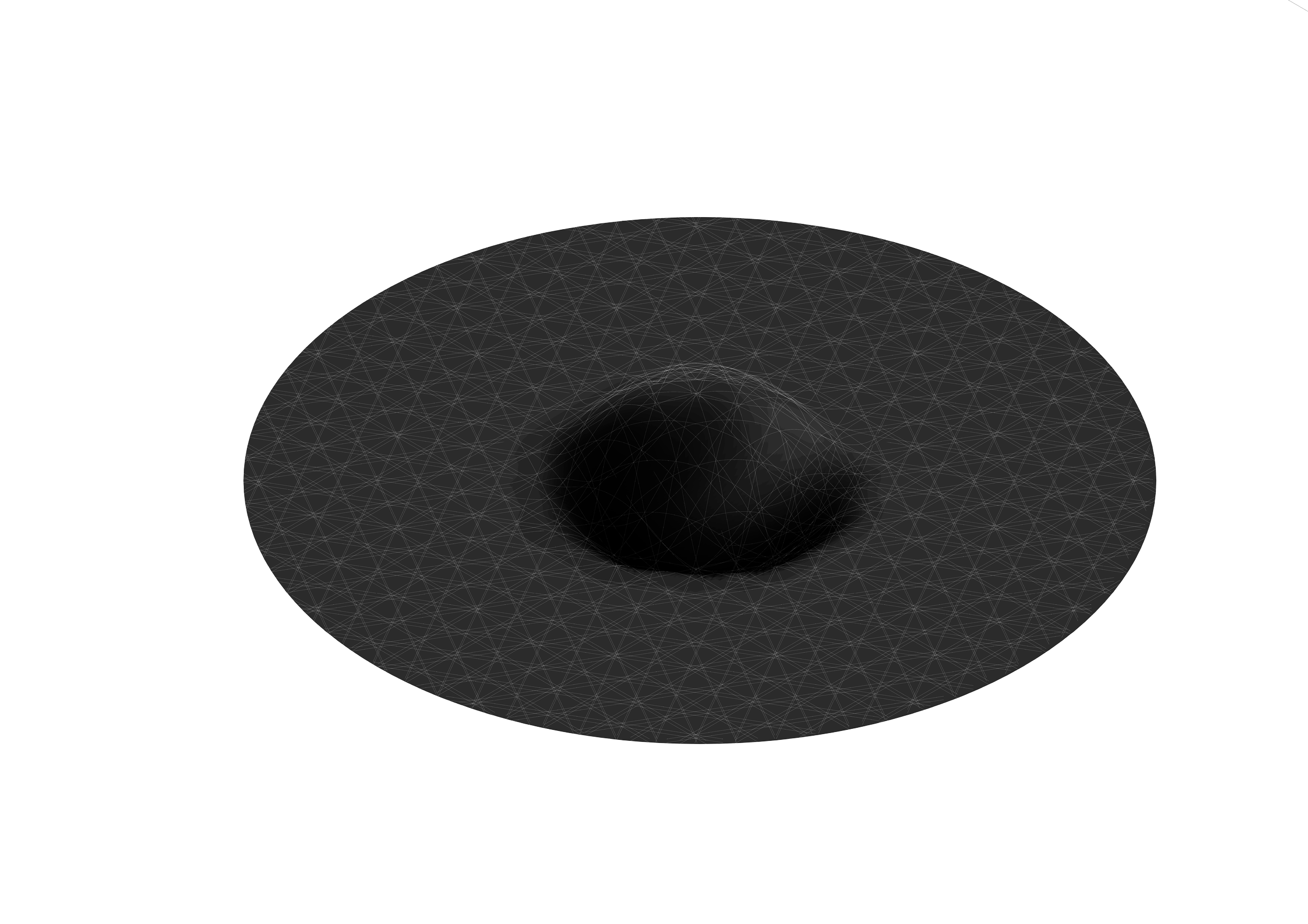

There was even a moment I tried to distort human cognitive perception by using Stuart Semple's Black 4.0 (the "blackest black" paint). I wanted to erase the depth of the object entirely. That experiment ended unfortunately, and we moved to a different finish. But these were necessary failures.

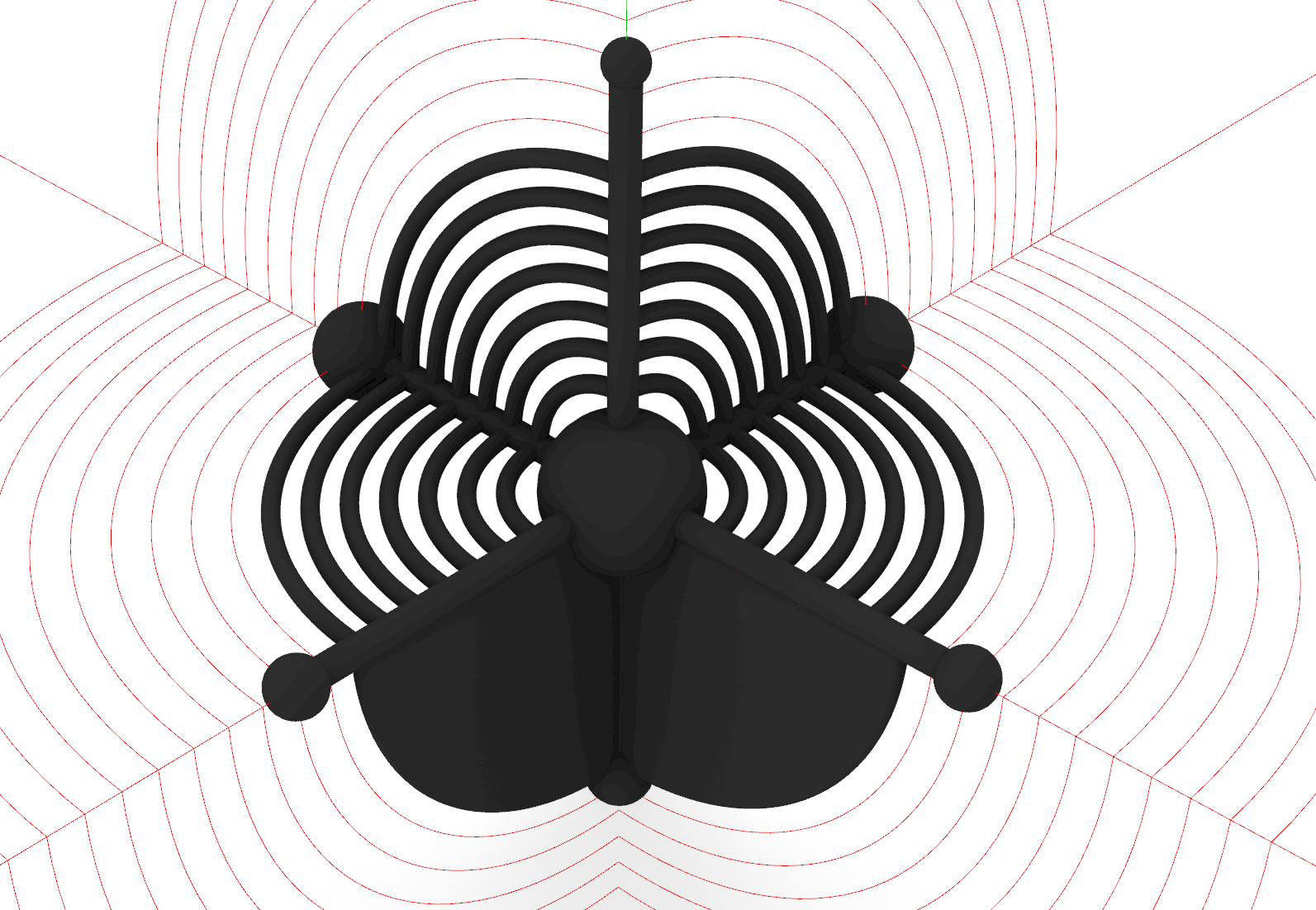

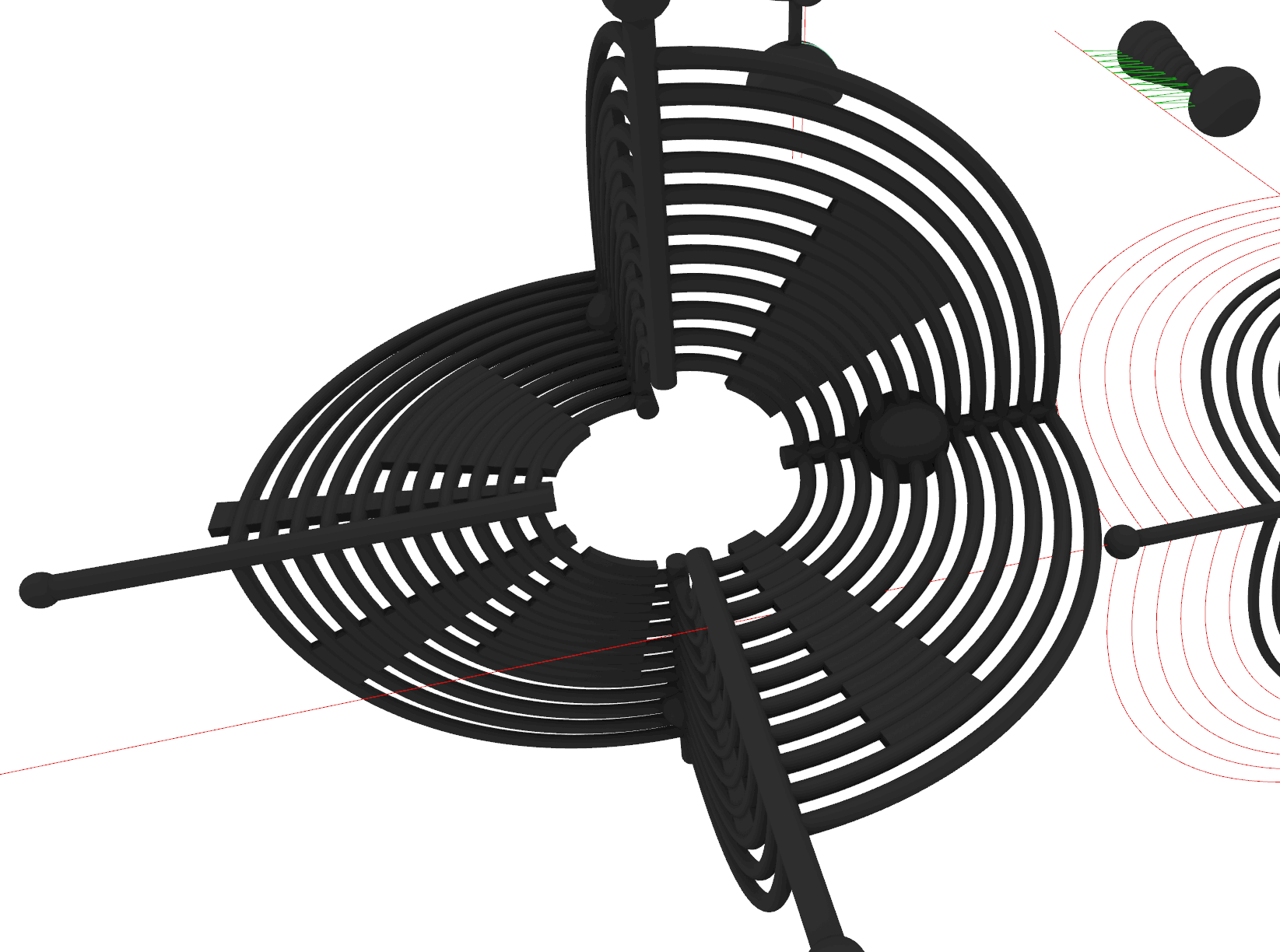

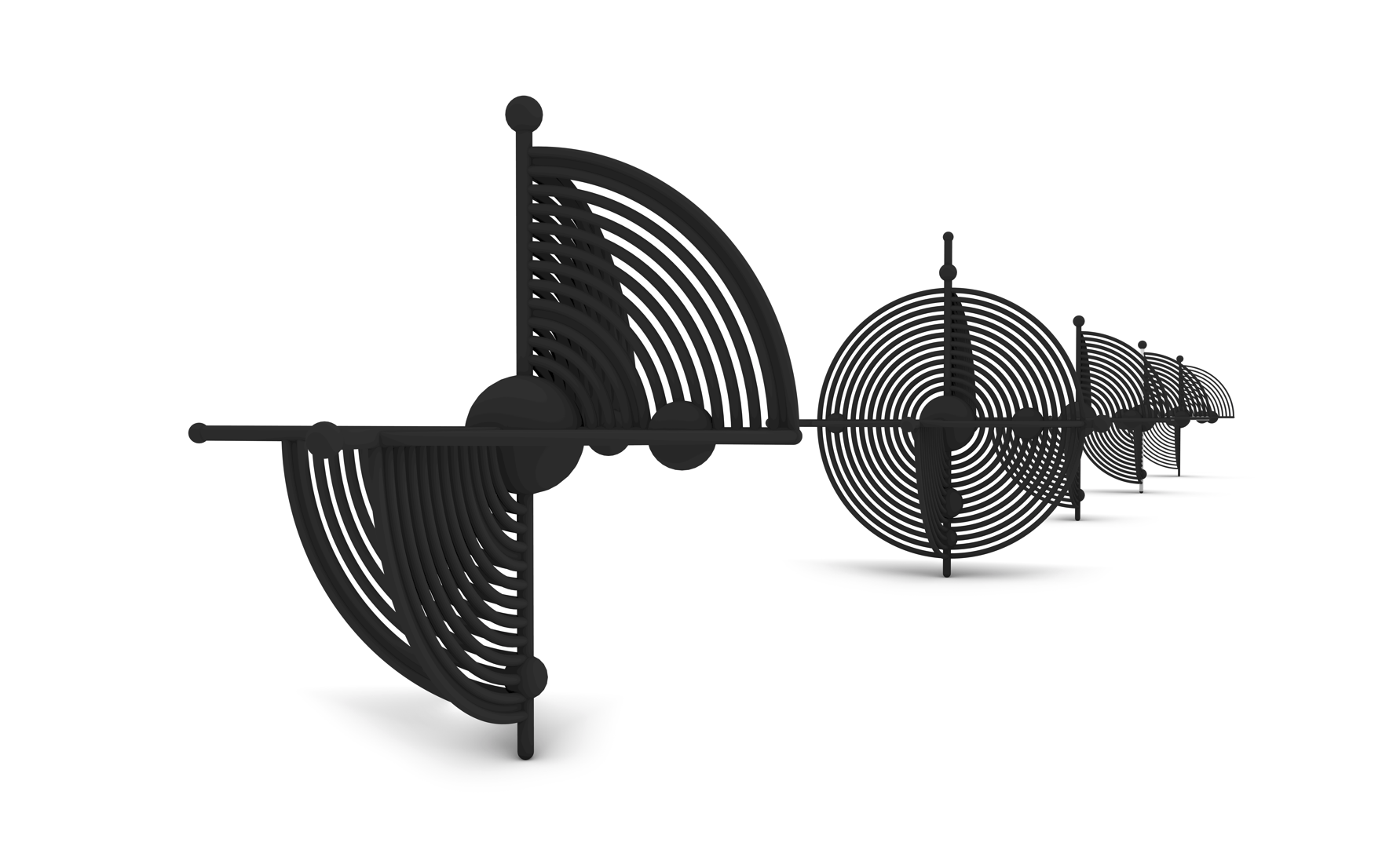

Early models

The Myth of the "Final" Form

I tell my students all the time: "Always expect changes; there is no such thing as the final design."

It is a horrible comment to hear, especially if you are a student right before the end of the term. Yet, I truly believe it. In every design, there is room for improvement. If a design seems flawless, perhaps you just haven't looked hard enough.

In architecture, with tight budgets and crazy schedules, we know a project cannot be "perfect." We simply make sure the essential requirements are as close to the vision as possible, making swift, decisive calls in the moment.

I do not believe in the "Final Form." I believe every design has an expiration date. In architecture, that date might be longer than a carton of milk, but it exists nonetheless.

The version you see at Songeun is simply the survivor of a rigorous process. It carries the DNA of all those failed 3D prints, the fidget spinner concepts, and the Black 4.0 experiments. It is the smallest object I have ever worked on, but it required the most intense focus I have given to a project in a long time.

Prototype and test of materials

Scaling Up for 2026

I am clearing these prototypes off my desk now. It was a refreshing exercise to obsess over micro-details—almost like a meditation.

But I admit, I am ready to zoom out again.

We have a project that has been quietly simmering for over a year—something much larger than a paperweight, involving actual walls and real gravity rather than just the cognitive kind. I look forward to sharing that change in scale with you in the New Year.

For now, thank you for following the journey of this tiny, heavy thing.

With all best wishes, and a very Happy New Year.

Upcoming project